|

THE ARCHITECT

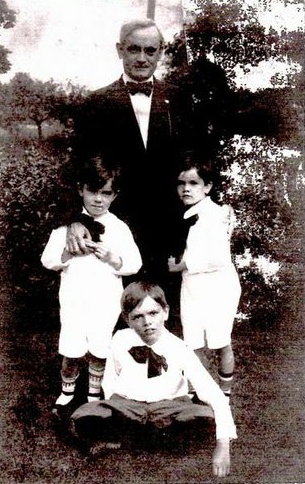

Zachary Taylor

Davis and three of his sons. From left; David, Lawrence, and William.

Tragically, William would not survive past age seven.

Alma Conant

Davis

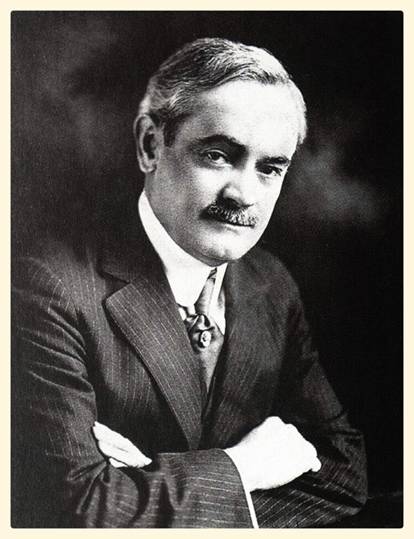

My

great-grandfather Zachary Taylor Davis was the personification of

an enigmatic and private person. Despite our prospering information

age, little remains to give

indication of his existence - with the exception of a few buildings; St. Ambrose Church

(1904), Kankakee Courthouse (1909), Wrigley Field (1914), St. James

Chapel of Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary (1918), and Mount

Carmel High School (1924),

His career began after he

graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago and served a six year

apprenticeship, which included working as a draftsman for Adler and Sullivan.

(Another young fellow named Frank Lloyd Wright was just about to leave

due to a breach of contract.) He then moved on to a position

as architect in residence with Armour and Co.

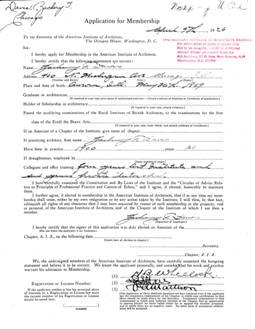

Zachary’s 1926

application for membership to the American Institute of Architects

In 1909, he designed the

Kankakee County courthouse. A year later, he was hired by Charles Comiskey to design Comiskey

Park for the Chicago White Sox. To prepare for the project, he toured

ballparks around the country with White Sox pitcher Ed Walsh. In 1914,

he designed Weeghman Park for the Chicago

Whales, a park which would later become Wrigley Field.

Zachary’s offices (1343

& 1345) were located in Chicago’s noted Unity Building, a structure

which would disappear as part of Chicago’s Block 37 project. When

mentioned in articles, he was simply referred to as “the architect.” More

often than not a piece would pertain not to him, but to one of his four

children; Zachary Taylor Davis II, Lawrence, David (my grandfather), or

Mary Louise. (Another son, William Taylor Davis died at age 7.)

During the latter part of

Zachary’s career (during the Great Depression - when work had dried up

for most architects) he became Superintendent of Repairs on Schools for

the Chicago Board of Education. When he died at age 77 on December 16,

1946 (at his home in the once fashionable South Side neighborhood of

Kenwood), services were held at the church he designed in 1904 - St.

Ambrose. He would be interred at Mount Olivet Cemetery, joining his wife

Alma, who predeceased him one month earlier.

“One of the most significant lost architects in Chicago.” – Family member

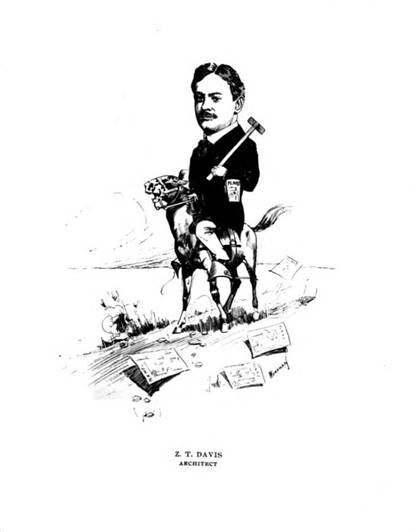

This caricature

of Zachary appeared in the book, Chicagoans

As We See ‘Em: Cartoons-Caricatures -

compiled by Frank Folwell Porter. Chicago:

Newspaper Cartoonists’ Association, 1904

HIS WORK

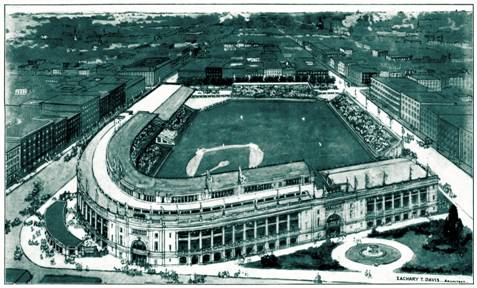

Comiskey

Park

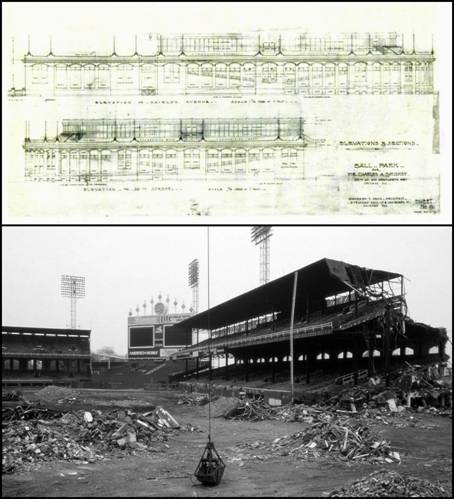

An original rendering

for the ballpark, c. 1910

Charles Comiskey’s “Baseball Palace of the World” under construction in 1910

Baseball fans line up

for tickets in 1914

Crowds cheer aviator Charles Lindbergh at Comiskey Park in 1927

The Beginning and the

End; Comiskey Park, 1910 – 1990

Wrigley Field

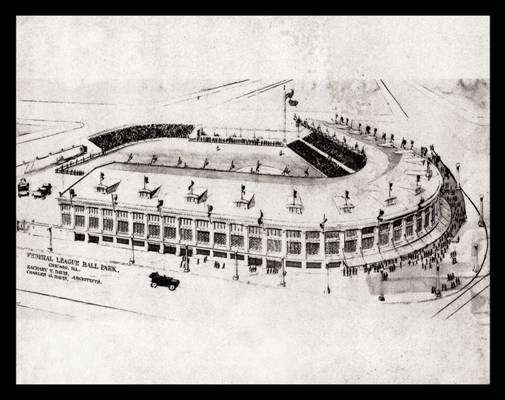

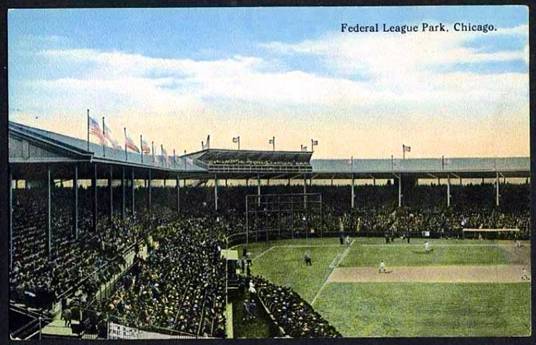

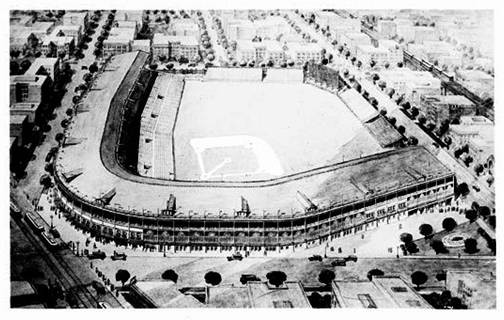

One of Zachary’s

renderings for the new Federal League Ball Park

Construction of the

ballpark in 1914, later named Weeghman Park – it would be

re-named Wrigley Field in 1926

The Park, c. 1915

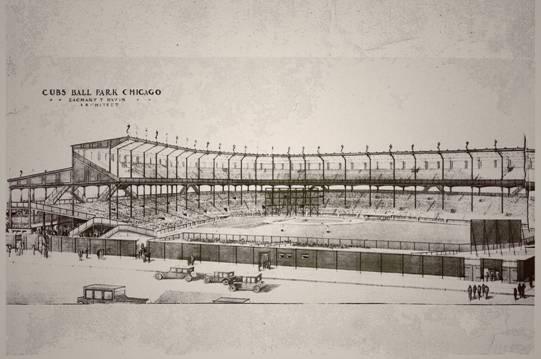

In 1922 Zachary would be

called back by William Wrigley Jr. for an upper deck expansion.

A Rendering of Wrigley

Field in 1929.

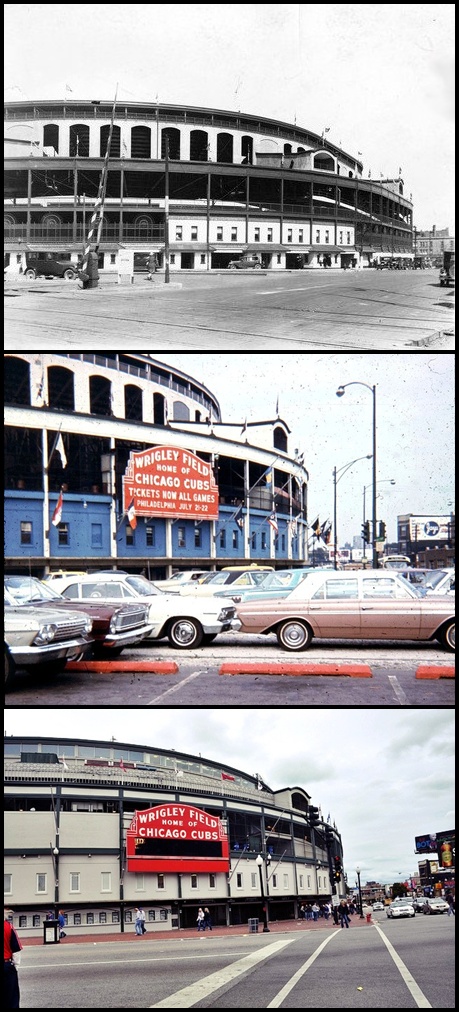

The exterior of the

ballpark in 1928, 1965, & 2010

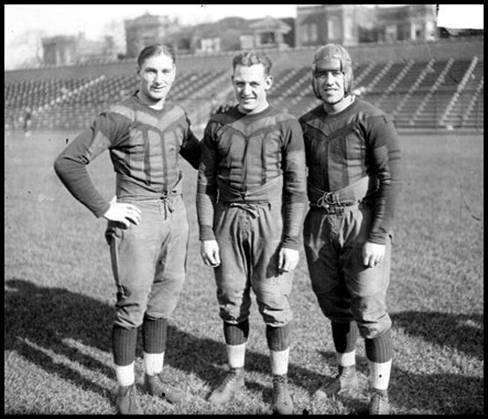

Chicago Bears at

Wrigley Field - 1925

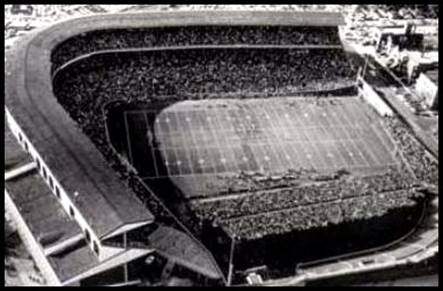

Wrigley Field set up

for a Bears game - The Bears played at Wrigley from 1921-1970

Wrigley Field

Los Angeles

In 1924, with the Los

Angeles Angels and their parent club, the Chicago Cubs under his

ownership, William Wrigley Jr. requested that Zachary design a ballpark

for him that had many of the characteristics of Wrigley Field in Chicago.

With a budget of

$1,500,000, the ballpark quickly became known as Wrigley’s “Million

Dollar Palace.” Unfortunately, Wrigley Field Los Angeles was demolished in 1965.

Oaklawn

Park

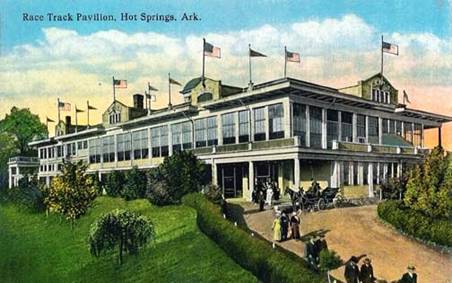

Hot Springs,

Arkansas

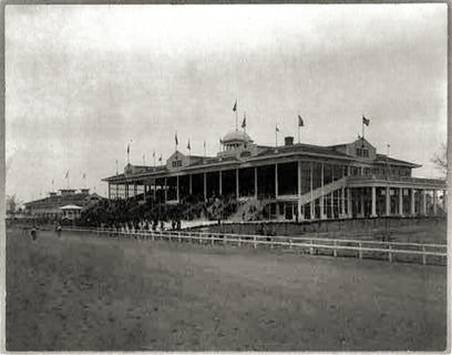

In 1904 Zachary

designed the clubhouse for Oaklawn Park race

track, and it officially opened on Feb. 24th, 1905.

Oaklawn

featured one of the first glass-enclosed and heated grandstands, and its

popularity was immediate with Midwest horsemen.

Speedway Park

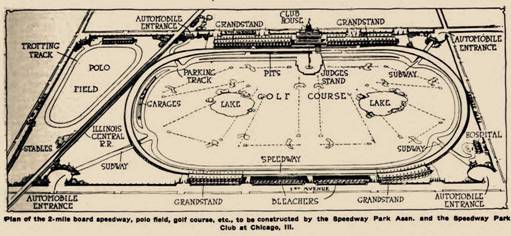

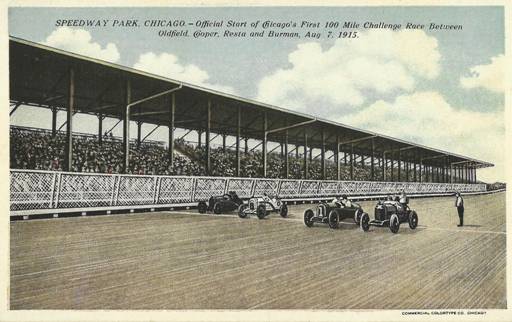

In

late 1914 (the same year as the Weeghman/Wrigley

Field construction) Zachary and his brother Charles G. Davis were

contracted to design Speedway Park – to be completed by June 1st,

1915.

At

the time, it was called the “fastest, safest and most spectacular

automobile race course in America.” Speedway Park was a mammoth two-mile

wooden board track located in Maywood, which operated between 1915 and

1918. For a brief period, it made Chicago the capital of worldwide auto

racing.

The

track was located on 320 acres of farmland just south of 12th Street

between First and Ninth Avenues with 22nd Street being the

grounds’ southern border. The amazing thing about the construction of the

speedway is that it was completed in the course of about 60 days, using

14 million feet of lumber supplied by timber baron Edward Hines. It

included 100 carloads of sewer and drain tile, 15,000 concrete piers,

50,000 cubic yards of cement, 500 tons of nails and spikes, 1,000 tons of

steel, 2,000 carloads of cinders and six miles of road approaching the

park.

The

park continued to operate during WWI, but after the summer 1918 season,

due to financial mismanagement and bankruptcy, it never reopened. The

track was dismantled, with the property being purchased and donated to

the U.S. government by Edward Hines Sr. for a veterans

hospital. It was called Public Health Service Hospital #76 for a time,

but was later renamed the Edward Hines Jr. Memorial Hospital in October

of 1921 in memory of Hines’ son, who died in France during WWI.

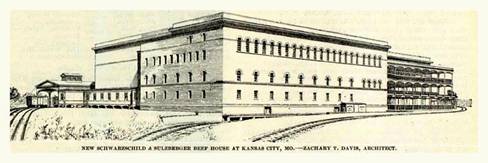

The Packing

Plants

Not long after

establishing his career as architect in residence for Armour

& Co., Zachary became the “go to” architect for packing houses across

the country. His plants incorporated the use of the most recent building

materials and technology at the time. Shown above is the rendering for a

packing house that was built for Schwarzschild & Sulzberger in 1898.

Kankakee

Courthouse

The Kankakee Courthouse

was begun in October of 1909 and completed in July of 1912. It is a fine

example of Beaux-Arts architecture, and in 2007 it was placed on the

National Register of Historic Places.

St. Ambrose

Saint Ambrose was built

in 1904 at the intersection of S. Ellis and 47th street.

Sadly, the steeple no

longer remains; when St. Ambrose was renovated in 2006 it was removed.

Although considered one of the most beautiful spires in the city, repairs

were estimated to be 1.2 million and the archdiocese could not absorb the

cost.

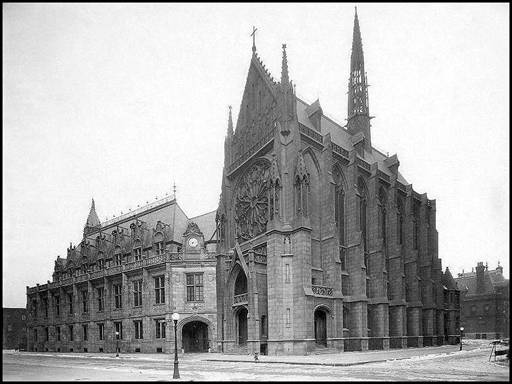

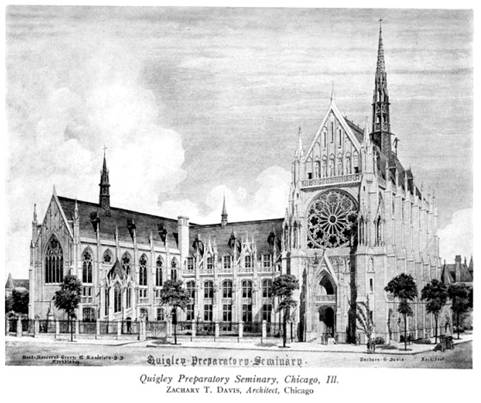

Archbishop

Quigley Preparatory Seminary and St. James Chapel

The exquisite St. James Chapel at Archbishop Quigley Preparatory

Seminary (dedicated in 1918) as it appeared in 1925.

The Quigley Center and

St. James Chapel today.

Take note that only the

base of the steeple remains. The original copper spire was damaged by a

wind storm in 1941 and permanently removed.

The magnificent

interior of St. James Chapel - viewed from the alter toward

the rose window on the west wall.

A rendering of Quigley

Memorial Seminary (ca. 1919) from the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club

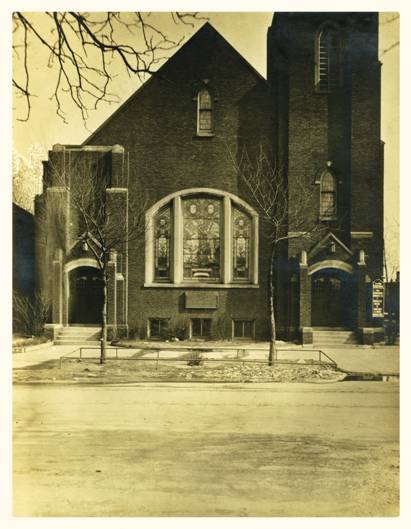

Drexel

Park Presbyterian Church

Construction

began in November of 1920 on the Drexel Park Presbyterian Church on the

northeast corner of Marshfield Ave. and Sixty-fourth Street. Zachary

designed a brick edifice with stone trim and 500 seats, including a

Sunday school in addition to the auditorium.

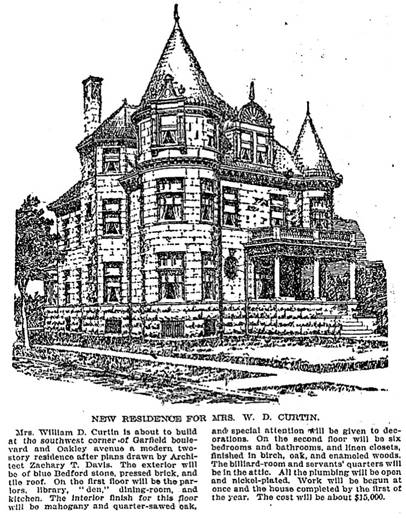

Residence

for Mrs. W.D. Curtin

This

house was designed during the summer of 1899 for Mrs. William D. Curtin

at the corner of Garfield Boulevard and Oakley Avenue. The house is still

extant as a residence.

James

Patrick O’Leary House

In 1901, this

house was completed at 726 West Garfield Boulevard for the successful

businessman/saloon owner James “Big Jim” O’Leary. O’Leary was only two years old when

the Great Chicago Fire began in the family’s DeKoven

St. barn.

O’Leary would

live at 726 Garfield until his death in 1925. The house is still

privately owned.

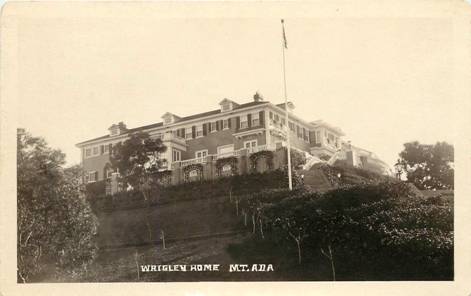

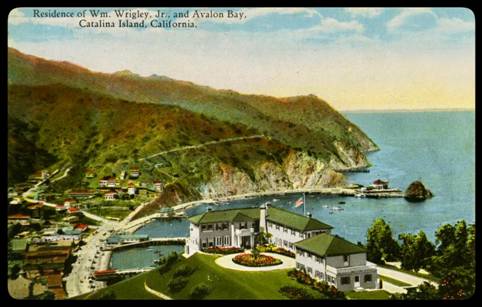

Residence for

William Wrigley Jr.

In 1919 William

Wrigley Jr. purchased a controlling interest in Santa Catalina Island,

off the coast of California. He immediately hired Zachary to design a

home for him atop Mt. Ada (named for Wrigley’s wife)

and the residence was completed in 1921 - the same year that the Cubs

started using the island for their spring training.

The Mt. Ada “summer cottage” had a commanding view of the

island.

Zachary designed

the “L” shaped mansion to wrap around a formal motor court entry on the

mountain side, with a graceful grand staircase of over 100 stairs leading

up to the house from the ocean side. The plan included three stories, a

Turkish bath, billiard room, organ chamber, and a refrigerating room.

There were six bedrooms, a sunroom, and an elegant terrace porch. Because

of the siting, William Wrigley watch the Cubs practicing from his mansion office.

Mount Carmel

High School

In December of

1922, Father Elieas Magennis,

General of the Carmelite Order, and Archbishop Mundelein of Chicago

agreed on the need for the immediate construction of a new St. Cyril High

School Building. In the spring and summer of 1924, the main high school

building was erected, with Zachary Taylor Davis as architect. In November

of that year the school was dedicated as Mount Carmel High School.

PROJECT PROPOSALS

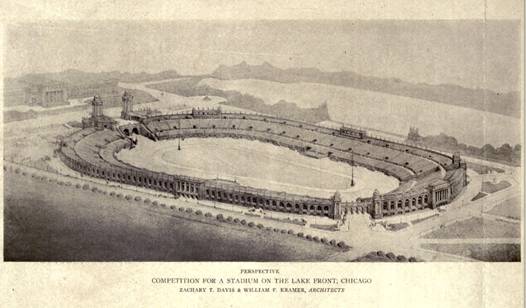

Soldier Field

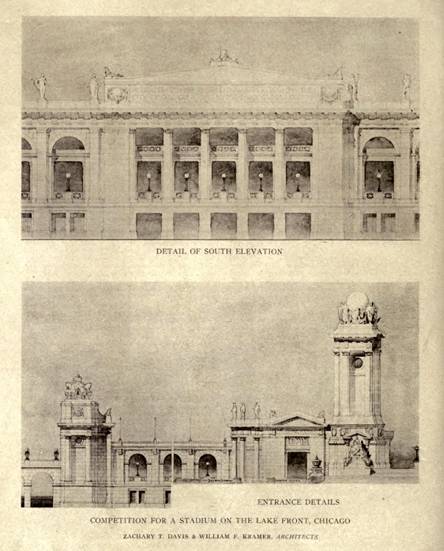

In 1920, several

Chicago architects were invited to compete in a competition to design a

lake front stadium in honor of WWI veterans. This is the plan submitted

by Zachary Taylor Davis and William F. Kramer.

Wacker Drive

Co-op Office Building

(click

to view)

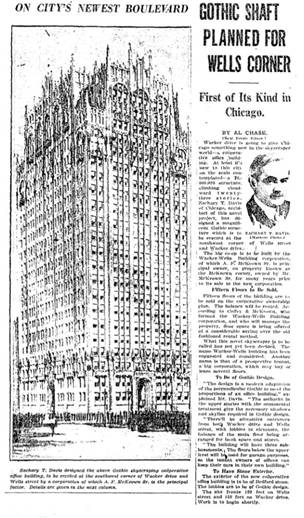

In 1926, the

Chicago Daily Tribune published a piece announcing the city’s soon-to-be

first co-op office building. Instead, two years later the Burnham Bros. Engineering Building at 205 W. Wacker,

rose instead.

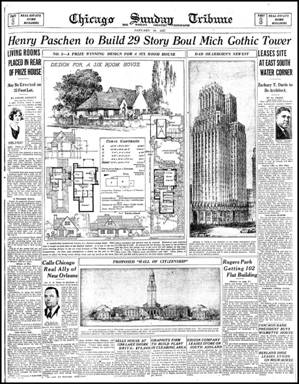

Boul

Mich Tower

(click to view)

In 1927,

developer Henry Paschen leased the site at the

southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and East South Water Street for

ninety-five years. Zachary Taylor Davis designed a twenty-nine story

Gothic skyscraper to be constructed at that location. One year later Paschen sold the leases, and in 1928 the Carbide and

Carbon building (designed by Burnham Bros.) was constructed.

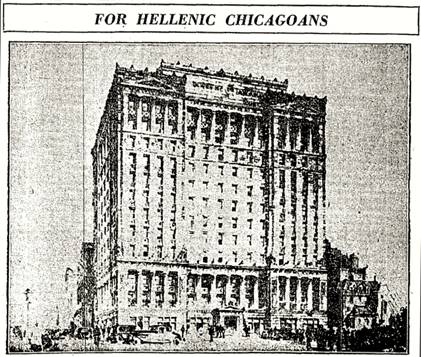

Hellenic-American

Athletic Club

In July of 1927,

the Chicago Daily Tribune announced that Zachary T. Davis had designed

this handsome structure which Chicago Greeks planned to erect on the Gold

Coast. It was to be called the Hellenic-American Club and the cost was

$1,250,000.

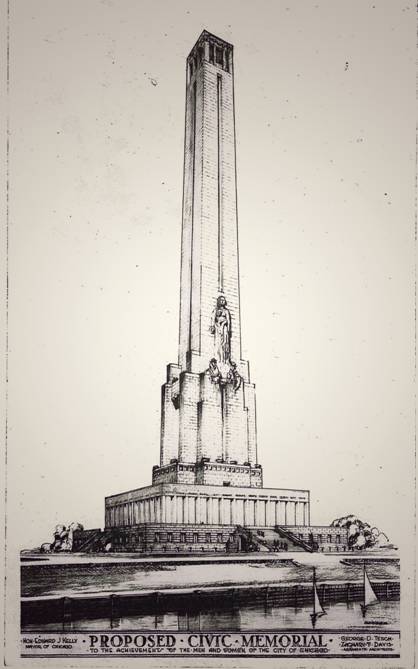

Civic Memorial

This project

originated in the first elective term (1935-1939) of Mayor Edward J.

Kelly. Kelly came to office from a long career with Chicago’s South Parks

Commission and Board (of which he was President). He played a powerful part

in the construction of major projects on the lakefront – such as Soldier

Field, the Adler Planetarium, and the Shedd

Aquarium. The Civic Memorial was never built, due in large part to the

Great Depression.

TERMINUS

Zachary’s

House

During the 1950s

and 1960s, a migration by homeowners to the suburbs and urban renewal

programs destroyed countless historic areas across the country, including

Chicago’s Kenwood neighborhood. This is Zachary’s home 934 East 45th

Street in January of 1965. Almost twenty years had passed since his

death, and the house was torn down not long after this photo was taken.

This address is now the site of Dr. Martin Luther King Junior College

Preparatory High School, a 4-year selective enrollment magnet high

school.

Zachary Taylor

Davis

May 26, 1869 –

December 16, 1946

EVERY human action gains in honour, in grace,

in all true magnificence, by its regard to things that are to come…

THEREFORE, when we build, let us think that we build for ever. Let it not be for present delight, nor for

present use alone; let it be such work as our descendants will thank us

for, and let us think, as we lay stone on stone, that a time is to come

when those stones will be held sacred because our hands have touched

them, and that men will say as they look upon the labour

and wrought substance of them, “See! This our fathers did for us.”

~John

Ruskin

::

Top ::

|